Sometimes, inspiration comes to me from strange sources: a fragment I read—or sometimes write—without knowing that its push and pull is inside me all along. Or the confusing beauty of a more natural sort, like the magnificent goldfinches outside my window, as they fight in a flurry of yellow over ownership of the last perch.

People often ask what I do for a living—especially over a plate of roast beef at dinner parties, when I admit that I am an author. Generally, they are not readers of my work. When they learn that my mother was a Pulitzer-Prize winning poet and sometimes even recognize her name, they are surprised to learn that I write professionally, too. Then they ask if I “do poetry,” and when I answer “No. All nine of my books are either fiction and memoir,” they look surprised.

I am hard put to explain exactly why this is so—as it feels too personal to reveal. I’m not sure I want to talk about it, but there the question sits, and I pause trying to speak the truth, despite my initial hesitation.

I have always been too afraid of the comparison that will inevitably arise, as that conversation always then turns to my mother’s fame and success. Nevertheless, comparisons like these do rain down on my head and on my soul. I so much wish I knew how to avoid them: there have been critics from the New York Times “Book Review,” declaring that my mother was far better than I at commanding power over language, or—worse—that my writing is filled with “purple prose.” Once Mom cautioned me: “Never be a writer, Linda, because I will follow you around like an old gray ghost.” Perhaps she has and it is true. Still, I don’t regret the choice I made when I set my first words down on the first page of my first novel, because she also said: “Linda, tell it true. Tell the whole truth.”

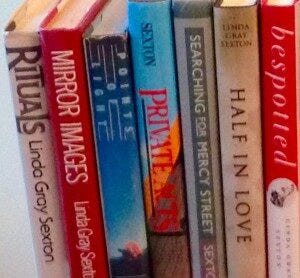

How difficult it has always been to declare myself a writer at all—yet there have been nine books on which my name appears as the author. Over two hundred or so of my “Linda’s Letters,” and a number of essays in Substack now. I’ve occasionally been featured In magazines or newspaper articles, and I’ve had the good luck to be assigned book reviews, as well. Searching for Mercy Street was deemed a New York Times Editor’s Choice and a Notable Book of the Year. But far more important are the readers who send me notes saying that what I’ve written has “changed"—or even “saved”—their lives. Their words are my true reward.

One day I clicked on an email from a stranger named Benjamin B., sometime after I had published a newsletter essay for “Linda’s Letters” about writing my first memoir, Searching for Mercy Street. He said that he appreciated the forgiveness I’d expressed toward my mother there—and that it was startling to him that I had written the book at all. His voice was a whisper in my ear, but I listened nonetheless. However, he expressed his doubt that I could have had any reservations about whether I had, in fact, command of the English language. Surely this could not be true, he said.

He wanted me to understand that despite my mother’s success and fame, both of which had hung me up for years, I was indeed a writer—perhaps even a poet of sorts. For over two decades, I have kept his email on my desktop computer, with his name as the author upon it. Even in my darkest moments, I could see that at least he understood what I was trying to do.

To my surprise, in addition to this email he had taken the courage to send, were two short poems—not his own words, but mine—using several consecutive lines from my first memoir. It was the first time I had seen anything written by me in the form of a poem since I was a teenager, working by my mother’s side.

Benjamin B. had broken some of my prose from Searching For Mercy Street into two different poems and told me that, despite my convictions that I was not a poet, at least the possibility existed within me—replete with imagery, cadence, format and the sound of the word. He was offering me, in this way, two of my own “poems” as proof. He could hear the poetry pushing through my prose, even though I would not have been able to see it that way previously. The mastery of the genre doesn’t really matter, he insisted; what matters is the cool water of imagination that feeds the warmer lake lying above it.

I am grateful that my mother passed along the love of both poetry and prose to me. Did she succeed in making me a poet? I don’t think so, though I am proud of Benjamin B’s attempt to turn one into the other. However, I am grateful that my “old gray ghost” did indeed try to give me such an appreciation. And perhaps, even in this version of “Linda’s Letters,” something new was pushing me to find my own sort of poetry, with the metaphor and the rhythm of language that have always guided me onward. Does it really matter what I call myself?

So, thank you, Benjamin B—for opening my mind and showing me all that I didn’t know was percolating inside me. I offer both “poems” to you, my readers, and ask not for the scour of your judgement, but for your simple appreciation instead. This is everything I have to give. Whether poetry or prose, I hope it is enough.

Litany of Despair

Depend on no one

Not the wide, empty sky

not the distant yellow moon.

Not the teacher, not a minister.

Not God.

Not grown-ups.

No one will give you what you crave:

a doll

a cuddle

permission to suck your soggy thumb.

No one will rescue you.

Above the next poem Benjamin B. wrote, “But on the next page you had these powerful life-giving words:”

Power

Power accompanies words:

the ability to speak your mind,

to tell your own story,

to say what you want,

to communicate.

This is a right

for which we fight

from the moment we discover

the ability to speak

during our second year of life.”

I am honored and grateful to have read all of your published works. Please remember that there are a ton of us out here who admire you, know who you are, and listen. You are genius in your own right, not just your mother's daughter.

Wow, Linda. What a gift Benjamin gave you by reflecting back your own words in poem form! I came to you and your work through SEARCHING FOR MERCY STREET a few years ago. I can't remember how it all began, except that I think I went down this poetry rabbit hole, and of course your mom was in that hole. Maybe someone had mentioned that a high percentage of poets end up suicidal, and that intrigued me because of my background in counseling. I wanted to understand who and why.

So I found some video about your mom, maybe a documentary? And you and your sister were in it. For some reason, that gripped my heart--seeing you as children in this video. I thought about my own publishing path and my own children and wondered what their perspective might be, whether they might inadvertently always feel compared to me one day.

And I wanted to know what it was like for you. That's when I found your book.

Linda, you are a gifted writer. You deserve that title. I think your mom was wise to warn you that she may always follow you like a ghost. She must've known in some way that her celebrity would follow you throughout your life. That, to me, speaks of a mother's love.

I also understand the feeling of telling people you are a writer and their weird responses. You have a whole different level of adding that your mom was this famous poet. The only thing I can conclude about these strange reactions is that people have either a romantic/idyllic perception of a writer's life, or they dismiss it as a hobby. They either are jealous of a writer, assuming that we all hole up in a cabin the woods to write in solitude (yeah, right--I have five kids), or we are "just playing around, and isn't that nice?"

It's really sad to me that these misconceptions about artists in general prevail in our society. At the same time, when I read your essays--just as when I read your memoir--I feel strengthened in my resolve to keep showing up. It's a sort of cultural defiance to me--to demonstrate that writers exist. That we have talent. That we have something to say. That storytelling is how we shape and remember. It's the bedrock of our society. Without the arts, an entire era would dissolve. The world needs our art. It needs yours and it needs mine. I am so grateful to be doing this with you, Linda.